🎯Too Long; Didn’t Read

The U.S. packs a ridiculous range of dives, from tropical coral gardens to freezing kelp forests and historic shipwrecks.

-

Keen on warm water? Florida's reefs burst with marine life. Dive wrecks such as the USS Spiegel Grove—it's enormous. Hawaii delivers geological thrills: explore volcanic lava tubes and formations. For a secluded spot, try the Flower Garden Banks off Texas. Corals remain untouched, and large pelagics frequently appear. Hawaii also offers night dives with manta rays.

-

Not the tropical type? California's Pacific coast delivers. The real magic happens below the surface around Monterey Bay and the Channel Islands. Here, giant kelp forests undulate, a canopy hiding a world that absolutely teems. It's a pulsating habitat. Sea lions dart, seals navigate the stalks, octopuses ghost between the roots.

-

History's another angle. The Great Lakes—their cold, deep waters preserve shipwrecks almost perfectly, which is pretty spooky. Shift to the East Coast, and North Carolina's "Graveyard of the Atlantic" is known for its massive number of wrecks, with sand tiger sharks frequently roaming the area. Up north, New York and Rhode Island deliver challenging wreck dives on vessels from the past.

-

Casual swim? No way. Diving these spots means you need to prep properly. Your gear shifts big time with the environment—rock a thin wetsuit in Hawaii's tropics, but switch to a sealed drysuit for the frigid Great Lakes. Certification level? Non-negotiable. It covers reefs for newbies and technical wrecks that demand pro skills. Plan ahead.

U.S. diving? Way more varied than folks assume. Florida delivers tropical reefs. California's kelp forests—prepare to freeze. Or hit the Great Lakes for shipwreck exploration. Every region brings its own vibe.

Florida Keys

The Florida Keys arc southward off the peninsula. The water stays warm, pretty much always. That constant heat is what pulls divers in.

For straightforward reef access on the East Coast, Key Largo is the spot. It houses John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, which protects part of the Florida Reef. This system ranks as the planet's third-largest barrier reef. The area teems with over 600 fish species. A bronze figure, the Christ of the Deep, stands at 25 feet. It draws a steady current of divers.

Then there's Molasses Reef. It gets packed for a reason. The payoff is real. Its formation creates swim-throughs and sand valleys. You can dive from a mere 10 feet down to 40.

The USS Spiegel Grove rests off Key Largo. A 510-foot landing ship, it was scuttled in 2002 to function as an artificial reef. Its sinking was an event—the vessel flipped before finally settling upright on the seafloor at 130 feet. Hardcore divers penetrate its interior. That takes skill; the currents there are no joke, a serious challenge even for the proficient.

Southwest of the Looe wreck lies a whole other scene: the reefs of Looe Key. Sanctuary status protects this area. You can find depths from a mere five feet to a solid thirty-five down. The place gets its name from the HMS Looe, an 18th-century British frigate that met its end here. These days, the seafloor is a serious jumble of brain coral, with elkhorn and staghorn formations crowding the space. And when the seasons shift, it becomes a highway for schools of tarpon moving through.

California

Diving California’s 840-mile coast means confronting the Pacific’s cold. A thick wetsuit isn’t a suggestion—it’s a necessity.

Monterey Bay dominates the scene. The place is a marine sanctuary, a 276-mile protected zone. Its hidden canyon dwarfs the Grand Canyon in depth. All that upwelling from the abyss brings in nutrients, which in turn brings in marine life. The numbers are just ridiculous.

Most divers get their start at Breakwater Cove. It’s a shore dive. Simple. You just walk in. Then you’re inside the kelp. Giant strands, 100 feet tall, block the sun. Harbor seals materialize out of the gloom. They might eyeball you with detached curiosity. Or they might get playful.

The forest floor crawls with life. Look for lingcod, rockfish, the odd-looking cabezon. Octopuses hide in crevices. And the nudibranchs—these sea slugs have color schemes that defy logic. As for visibility, it’s a gamble. You could get 60 feet of clarity or 10 feet of murk. It all depends.

Channel Islands National Park lies off Santa Barbara's coast, a remote spot you can only reach by boat. That isolation is precisely why the reefs remain intact—not stripped bare like others. For kelp diving, skip Monterey's murk; Anacapa has clearer water. You’ll encounter California sea lions there. They’re bigger and more assertive than harbor seals, no joke. They’ll buzz you, barrel-roll past, and basically act like oversized ocean puppies.

Then there's the Painted Cave on Santa Cruz Island. It’s the planet’s largest sea cave. Kayakers flock there, but divers can probe the entrance. The area also holds wrecks, like the Winfield Scott, sunk in 1853.

Hawaii

Hawaii's volcanoes built this place from the Pacific floor up. That geologic drama shapes what's underneath the waves. Oahu has something for everyone.

New to snorkeling? Try Hanauma Bay. The water sits inside a volcanic crater—calm, protected. You’ll spot parrotfish and triggerfish. Green sea turtles are common. Heads up: the place gets swamped during peak hours.

For a next-level dive, the YO-257 wreck sits 100 feet deep off Waikiki. The Navy used this vessel as an oiler. They sank it in 1989. Now it’s an artificial reef. White-tip reef sharks patrol the exterior. Eagle rays drift past. You can find turtles sleeping inside the structure itself.

Over on Maui, the leeward coast’s calm waters make turtle encounters almost a guarantee.

For lava tube exploration, head to Five Caves and Five Graves—two names for one site. These tunnels were created by lava flows that crusted over on the surface while the molten core drained out. Look for white-tip reef sharks tucked into the rock, sleeping through the day.

A three-mile trip from Maui’s south coast brings you to Molokini Crater. This crescent of volcanic rock juts up from depths of 300 feet. Its protected interior wall plunges to 150 feet. Visibility can stretch past 100, a clarity that sometimes reveals manta rays. The crater’s backside is a different world. It confronts the open ocean, where currents surge and hammerheads circle.

On the Big Island, the manta ray night dives are next-level. After sunset, boats anchor along the Kona coast. Lights pierce the water, concentrating the plankton. Mantas arrive to feed. They execute barrel rolls directly overhead, their wingspans stretching to 15 feet. The experience is surreal, a complete perspective shift. It’ll mess with your head.

North Carolina

The Graveyard of the Atlantic is a body count. North Carolina's Outer Banks alone tally over 5,000 shipwrecks. This happens because two ocean titans brawl here. The warm Gulf Stream pushes north. Arctic currents shove south. Their collision zone can flip from serene to savage fast.

Take the USS Huron. This iron steamer, a Navy gunboat, sank off Nags Head in 1877. Now it rests in just 62 feet of water. From May to October, the wreck becomes a shark hangout. Sand tiger sharks congregate. On one dive, you could spot dozens. Maybe fifty. Their needle teeth give a permanent snarl, but the vibe is surprisingly chill. They just cruise the wreck, a ghostly patrol.

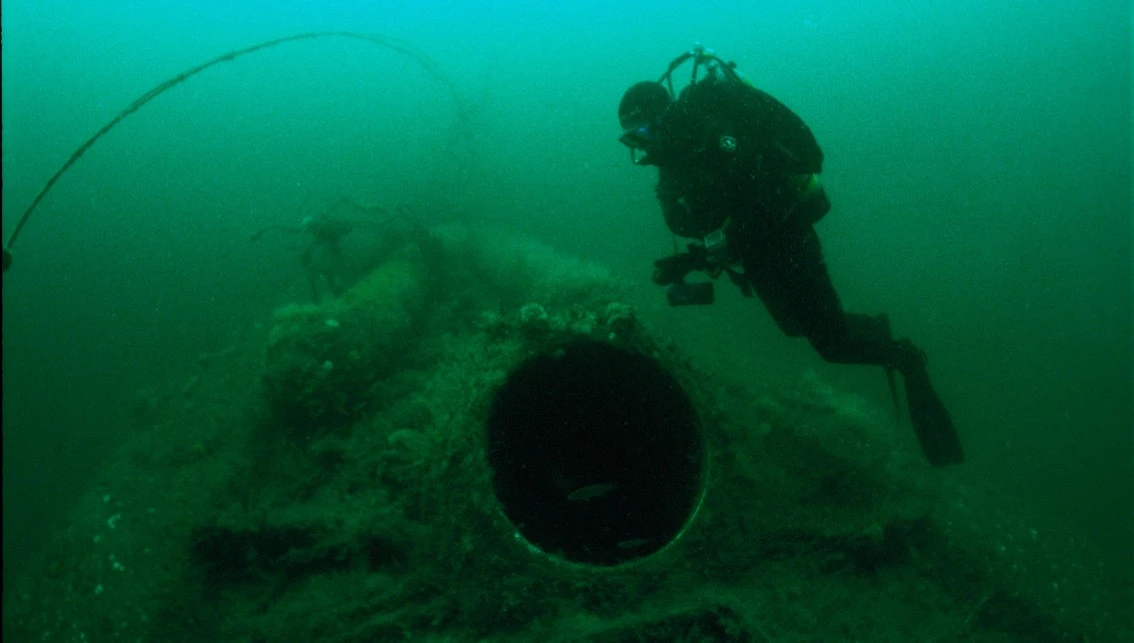

The German U-boat U-352 went down in 1942. It lies in 115 feet of water, upright. You can make out the conning tower, the deck gun, the torpedo tubes. Time and the ocean have taken a toll; the wreck has definitely succumbed to decay. Yet its history pulls divers in. It’s a ghost town vibe down there.

Then there's the USS Indra, a 180-foot freighter. She sits shallower, at 60 feet. On a good day, visibility can stretch to 80 feet—crystal. The wreck is now a magnet for marine life. Spadefish, amberjack, barracuda patrol the structure.

Great Lakes

It’s easy to forget that the Great Lakes are a massive shipwreck graveyard. Superior alone contains ten percent of the planet's surface freshwater. That deep cold acts as a preservative, slowing decay that would ravage a wreck in saltwater.

Superior's clarity is legendary. Visibility can hit 100 feet. The cold has a brutal honesty to it; a summer dive still demands a drysuit.

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald remains a tomb. Lost in 1975 with all 29 hands, the site is respected per the families' wishes. It’s strictly off-limits. Many other wrecks, however, are open for exploration.

Take the America. This passenger steamer went down in 1928 near Isle Royale National Park. It rests at 80 feet. The bow is completely intact. You can make out the windlass—used for hoisting anchor—and the bollards for securing lines. The rule is simple: look, but don't lay a finger on it.

Shipwrecks dot Lake Michigan's Wisconsin and Illinois shores. For example, the Appomattox—a three-masted schooner lost in 1905—lies in mere 16 feet of water near Shorewood. Freedive it easily.

Over in Lake Huron, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary safeguards 200-plus wrecks. Among them, the Nordmeer, a German freighter sunk in 1966. Its depth? A hefty 185 feet. Strictly technical diving territory.

Washington

Puget Sound's diving is seriously underrated. Yeah, the water's cold—often brutally so. Visibility can be a gamble, turning the world into a murky green haze. But that's the price of admission. The payoff is a marine life scene that's absolutely wild.

This place is a stronghold for the Giant Pacific octopus. We're talking about an animal that can hit 100 pounds, its arms stretching 20 feet. Spotting one is a trip. You might find it coiled inside a rocky crevice, watching you. Then it happens: its skin shifts color and texture, a live, seamless match to the stone. It’s mind-bending camouflage, not just a trick you see on a screen.

Dive straight from the shore at Edmonds Underwater Park. Sunken structures build artificial reefs there. Spot rockfish, lingcod, Dungeness crabs. Wolf eels conceal themselves in crevices—they’re not true eels, just fish. Bulbous heads and powerful jaws give them a prehistoric appearance.

Over in Possession Sound, the Honey Bear wreck rests. This 1920s tugboat was sunk to create a reef. Plumose anemones now envelop the structure. Perch schools swarm around it.

Texas

The Flower Garden Banks are a hundred miles out, past the Texas-Louisiana border. These are the continental US's most northern coral reefs. Getting there demands a commitment: a liveaboard or a marathon boat trip.

The reefs themselves loom up from the abyss, over 300 feet deep, stopping just 50 feet from the surface. Their structure is built from brain coral, star coral, and fire coral. Manta rays are regulars. Deeper down, hammerhead sharks patrol. In summer, the big ones—whale sharks—cruise through.

This isn't tame Caribbean diving. Currents here pack a punch and conditions can flip fast. That same isolation, however, is what keeps the reefs pristine.

New York

The waters off Long Island offer a portal to the past, a world of wreck diving. Take the USS San Diego, an armored cruiser that met its end in 1918. A mine sent it down. Now it lies silent in 110 feet of water, the sole American warship from World War I to sink in US waters. The vessel is completely inverted. This upside-down posture exposes its massive propellers and rudder. Sea life has moved in; lobsters now crawl across the steel hull.

For the truly audacious, there’s the Andrea Doria. This Italian liner rests in a much more formidable 250 feet off Nantucket. It sank following a 1956 collision. That depth, combined with brutal currents and the wreck’s advanced decay, creates a lethal environment. Over a dozen divers have lost their lives here. Exploring it requires serious chops—this is strictly for technical divers with the right skills and nerve.

Rhode Island

At Fort Wetherill State Park, you just walk in from the Jamestown shore. Submerged granite forms tight caverns and tunnels to navigate. Lobsters scuttle across the bottom, hiding among cunner and tautog. Even when visibility drops to ten feet, the complex landscape keeps things engaging.

Speaking of depth, the U-853 wreck sits 130 feet down off Block Island. This German U-boat sank just before World War II ended. It's fully intact and upright on the seabed. The conning tower and deck gun remain clearly visible. Reaching them is the real challenge; you'll be wrestling with strong currents. This dive is strictly for those with advanced skills.

Planning Your Trip

-

Water temperature matters. Florida and Hawaii stay warm year-round. California, Washington, and the Great Lakes require exposure protection. Check conditions before you go—some sites are weather-dependent.

-

Certification levels vary. Shallow reef dives work for Open Water divers. Deep wrecks need Advanced certification. Technical wrecks require specialized training. Don't dive beyond your limits.

-

Some sites require guides. Channel Islands and Flower Gardens need boat charters. Many wrecks are offshore. Shore diving works at Monterey, Edmonds, and various Florida locations.

The US offers diversity. You can dive into different environments without leaving the country. Cold-water kelp forests test your skills differently than tropical reefs. Wreck penetration provides different thrills than drift diving. Try different regions.

What You'll Need

-

Your basic scuba setup works for most locations. Tropical diving needs a 3mm wetsuit or less. California and Washington require 7mm wetsuits or drysuits. Great Lakes demand dry suits unless you enjoy hypothermia.

-

Wreck diving adds requirements. Lights help inside structures even during the day. Reels help with navigation. Cutting tools are standard safety equipment. Don't penetrate wrecks without training.

-

Some locations need boats. Factor in charter costs. Liveaboards run expensive but maximize dive time. Shore diving saves money.

-

Book in advance during peak season. Florida gets packed in winter when northerners flee cold weather. Hawaii stays busy year-round. California diving is best late summer through fall when visibility improves.

❓FAQ❓

Do I need a scuba certification to dive in these U.S. sites?

Yep, you'll need at least an Open Water Diver certification. Get it from recognized outfits like PADI or SSI. Planning deeper dives or wrecks? Then advanced or specialized certs are required.

How long does it take to get a basic diving license?

Typically 3-5 days, the PADI Open Water Diver course covers theory, confined water training, and open-water dives. It gets you certified for maximum depths around 60 feet (18 meters).

What are important safety tips for wreck diving?

Start with a solid dive plan—map it out thoroughly. Bring extra gear; dive lights and reels are essentials. Get your buoyancy dialed in. Hands off wrecks; no touching or removing anything. Dive within your limits to dodge hazards like currents and entanglements.